Dear Lily June,

Okay, prepare to hate this. But the thing is, your mother was a former teacher of English (composition, literature, creative writing; you name it, I taught it). And as such, she has all these old lessons just sitting on her computer desktop collecting digital spider-webs and e-dust or whatever. So I’ve decided, since I no longer teach in the classroom, I can at least occasionally refer back to some of my old lecture notes and teach you a thing or two about some important writers and techniques of writing. You hate this already, don’t you? I’m just so glad I’m sitting out of spitball range.

And here’s the thing: I’ll clearly label these for you so you’ll know which ones they are. So you (and any of my blog readers) can just skip them if they’re not your “bag”. Until, of course, it’s time to cram for that all important Lit exam. And then, my darling daughter, you might be glad to have these to turn to. I guess we’ll see if they ever have any use. I won’t “teach” these in any order that makes sense. I’ll just randomly refer back to whatever piece strikes me at the time. And today, since there’s a nip in the air and, as with any other day, I’m poor as hell, it’s F. Scott Fitzgerald’s “Winter Dreams.”

***

Read “Winter Dreams”

Okay, first lesson of literature first: If you’re going to analyze a piece of writing, you need to actually read it. No, seriously, Lily. You need to actually read for your classes. For real. I’ll wait here while you do just that. Here’s Fitzgerald’s “Winter Dreams.” Get reading, kiddo. [Thanks to whoever Mr. Gunnar from English 10 is for posting the .pdf online!]

***

Read for Yourself

Okay, second things second: Read for yourself, not for your teacher. Any teacher who tries to just have you memorize his/her interpretation isn’t teaching at all; they’re summarizing for you. I wasn’t that kind of lecturer. I’d give my students bread crumbs, but it was up them to follow them through the woods, so to speak. I taught by what’s called The Socratic Method, Lily, meaning I asked a lot of questions. Like, a lot a lot. So that’s a lot of what these blog posts will be: Me firing off questions that you can consider when and if you ever read the literature I’m referencing. (I hope you do, but no pressure. Reading has been a joy in my life, but it may not be in yours. And as always, I want you to make your own choices about what your path will be.)

But, yes, since you will have to do some reading for school, I advocate reading narcissisticly. A great piece of literature should be a mirror. A lot of times, the author’s dead (or when he/she isn’t, they’re still not likely someone you’re currently rubbing elbows with), so there’s no point trying to find their meaning in it. Find your own meaning. Find things to connect with, reject. Find characters you love or hate or love to hate or hate to love. Find lines to carry around in your pockets like loose change.

For instance, here are some lines I love from “Winter Dreams”:

“…the wind blew cold as misery.”

“Fall made him clinch his hands and tremble and repeat idiotic sentences to himself, and make brisk abrupt gestures of command to imaginary audiences and armies.”

“The helpless ecstasy of losing himself in her was opiate rather than tonic.”

- What lines, if any, do you love?

- What lines, if any, do you hate?

- Are any of the characters worthy of your adoration or ire?

- How do you feel about the author himself, Fitzgerald, after reading it?

***

Know When You’re Dealing With

While you’re not trying to come up with a dead man’s intentions (why would you? He’s dead), it helps to understand a story if you understand who the author was and when he/or was writing.

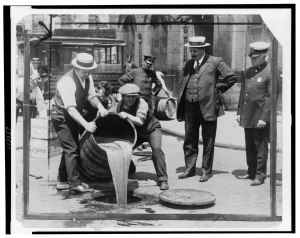

“Winter Dreams” was written in 1922, almost a hundred years ago (maybe more by the time you read this). The 1920s were a strange time, bound up in both Prohibition (when the United States tried to outlaw alcohol which, surprise surprise, didn’t work) and rebellious excess. America was booming, economically, from having exited World War I, and so, in terms of money, it was a time of luxury.

In terms of confidence in the country, though, to some, it was a time of poverty. You see, Lily, Fitzgerald was a member of two groups: the Modernists and the Lost Generation. He was a man who’d followed the growth of American industry–its entrance into modernity with the rapid invention of new technology–and who had been raised on Greek tales of the epic glory of the battlefield.

But when he went off to war–like so many young men of his age seeking to strike their fortune–and was forced to encounter, en masse, death and destruction, he returned without faith in either God or country. (See how important literature is, Lily? It can sway the beliefs of entire generations, this one called “Lost” or alternately, in French, Génération au Feu, a Generation in Flames.)

***

Know Who You’re Dealing With

But more than just a war story–or a story of a man going off to make his fortune in the world–“Winter Dreams”–and Fitzgerald’s own biography–are love stories. They are stories of men who equate wealth and woman into the same prize. For Fitzgerald, the woman was Zelda, and courting her meant making enough money to woo her with.

This is why I say that Fitzgerald had no imagination. His life-story of being a young man whose family lost their wealth, so he had to go to war–and, equally as brutal, New York–to make money as a soldier and writer in order to “earn” and “keep” his wife (a woman who went mad while he crawled into a bottle to keep sane) is a good one. But it’s the same well he kept revisiting, first with “Winter Dreams” and later in a more expansive way with his most famous The Great Gatsby. [I admit; GG’s one of my favorites. Hello, gift idea for Mama.]

***

Think of the Story’s Critique of Consumerism

Of course, Fitzgerald’s pairing the pursuit of women with the pursuit of wealth wasn’t all that uncommon. Think of the American Dream, Lily. Immigrants were coming in droves to America to seek their own fortune, and what did they first spy by boat on the way to Ellis Island? None other than Lady Liberty herself.

The term “American Dream” wouldn’t be “coined” (pun intended) until the 1930s, by a historian named James Truslow Adams, but the concept was in play long before that. And the idea of being disillusioned by the deeply consumerist bent of this “dream” is about as old as the dream itself.

Things to consider in reading the story:

- How would you define “The American Dream”?

- In what ways is courting Judy Jones made into the narrator’s, Dexter Green’s, pursuit of happiness? (What’s the possible significance, for instance, of their last names?)

- How, and why, do Dexter’s “winter dreams” fail him? Were these failures inevitable, and if so, why?

***

Think of the Theme of Fortune-Seeking

It’s interesting that “The Lost Generation” is a moniker now being applied again–and for a different reason–to your own parent’s generation. Your dad and I have “come of age” in a time of economic crisis in America–with corrupt bank lending, an increasing national debt, and crippling amounts of student loan debt altering the ways we make, or fail to make, our “fortune.”

- How do you define success, Lily? Is it the same way your generation would?

- Is there a cultural reason your success is becoming more difficult to attain?

Here’s a chart from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics from 2014 on how Americans spend their money. Have things changed much by the time you’re reading this?

Table A. Average annual expenditures and characteristics of all consumer units

and percent changes, 2012-14

________________________________________________________________________________

Percent change

Item 2012 2013 2014 2012-2013 2013-2014

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Average income before taxes $65,596 $63,784 $66,877 -2.8 4.8

Average annual expenditures $51,442 $51,100 $53,495 -0.7 4.7

Food 6,599 6,602 6,759 0.0 2.4

Food at home 3,921 3,977 3,971 1.4 -0.2

Food away from home 2,678 2,625 2,787 -2.0 6.2

Housing 16,887 17,148 17,798 1.5 3.8

Shelter 9,891 10,080 10,491 1.9 4.1

Owned dwellings 6,056 6,108 6,149 0.9 0.7

Rented dwellings 3,186 3,324 3,631 4.3 9.2

Apparel and services 1,736 1,604 1,786 -7.6 11.3

Transportation 8,998 9,004 9,073 0.1 0.8

Gasoline and motor oil 2,756 2,611 2,468 -5.3 -5.5

Vehicle insurance 1,018 1,013 1,112 -0.5 9.8

Healthcare 3,556 3,631 4,290 2.1 n/a

Health insurance 2,061 2,229 2,868 8.2 n/a

Entertainment 2,605 2,482 2,728 -4.7 9.9

Cash contributions 1,913 1,834 1,788 -4.1 -2.5

Personal insurance 5,591 5,528 5,726 -1.1 3.6

and pensions

All other expenditures 3,557 3,267 3,548 -8.2 8.6

n/a - Because of the questionnaire change for health insurance, the 2013-14

percent change is not strictly comparable to prior years.

________________________________________________________________________________

Notice that the average American in 2014 spent upwards of $1700 on clothes alone. (Note: expenditures in the standard report appear much larger than your own family’s. Sorry!) Dexter Green makes his money off of clothing–through laundromats–and says, “to be careless in dress and manner required more confidence than to be careful.”

- Do we still live in a culture where appearance matters so much?

- Do clothes, Lily, still make the (wo)man?

- What does that quotation above (about carelessness) mean to you? Is its claim still true?

***

Think of the Theme of Romance

It’s interesting, Lily. Most people flub up the Biblical quotation, saying that “Money is the root of all evil.” But in 1 Timothy 6:10, it reads, in fact, that “…the love of money is the root of all kinds of evil.” In some ways, Dexter and Judy play that argument out to the limits of its logic.

Think of lines like

“…the sad luxury of her eyes.”

“…kisses that were like charity, creating want by holding back nothing at all.”

“…he had put her behind him, as he would have crossed a bad account from his books.”

- What other descriptions of Judy–or of Judy’s and Dexter’s relationship–use the language and metaphors of money, finance and accounting?

- If loving Judy is like loving money, what does it mean that Judy loses her luster at the end? What does it mean that Dexter has “made money,” but can’t make Judy love him?

- In what ways are love and money–or sex and money–paired in today’s culture?

***

Think of Yourself

Ultimately, the test of a good reading isn’t whether or not you reached the interpretation the author intended. What matters is that you learned something for yourself, about yourself or your culture.

- How does this story apply to you? What can you take from it?

- What does it caution you against? What does it encourage you towards?

- How are you like Dexter? Like Judy? Like neither?

May your dreams be so much wider, and so much more attainable, than Dexter’s, my daughter. Thanks for reading with me!

***

Picture Credits:

- “F Scott Fitzgerald 1921” by The World’s Work – The World’s Work (June 1921), p. 192. Licensed under Public Domain via Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:F_Scott_Fitzgerald_1921.jpg#/media/File:F_Scott_Fitzgerald_1921.jpg

- “Bundesarchiv Bild 183-13055-0008, Hohendorf, JP mit Dorflehrer” by Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-13055-0008 / CC-BY-SA 3.0. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 de via Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bundesarchiv_Bild_183-13055-0008,_Hohendorf,_JP_mit_Dorflehrer.jpg#/media/File:Bundesarchiv_Bild_183-13055-0008,_Hohendorf,_JP_mit_Dorflehrer.jpg

- “Schneeflocken in Deutschland – 20100102” by Sara2. Licensed under Public Domain via Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Schneeflocken_in_Deutschland_-_20100102.jpg#/media/File:Schneeflocken_in_Deutschland_-_20100102.jpg

- “5 Prohibition Disposal(9)” by Unknown – Vintage periods. Licensed under Public Domain via Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:5_Prohibition_Disposal(9).jpg#/media/File:5_Prohibition_Disposal(9).jpg

- “DancingFlames” by Oscar. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:DancingFlames.jpg#/media/File:DancingFlames.jpg

- “Zelda Fitzgerald portrait” by en:Image:Zeldaportrait.jpg, originally scanned from “Zelda” by Nancy Milford. Scanned by en:User:Pantherpuma. Licensed under Public Domain via Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Zelda_Fitzgerald_portrait.jpg#/media/File:Zelda_Fitzgerald_portrait.jpg

- “Statueofliberty” by GaMeRuInEr at English Wikipedia – Transferred from en.wikipedia to Commons.. Licensed under Public Domain via Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Statueofliberty.JPG#/media/File:Statueofliberty.JPG

- “US Debt Clock 15-09-2009” by Johan Fr Øhman. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:US_Debt_Clock_15-09-2009.JPG#/media/File:US_Debt_Clock_15-09-2009.JPG

- “Striptease” by Michael Albov (aka mikegoat) – http://flickr.com/photos/mikegoat/2591986496/in/set-72157605552843111/. Licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 via Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Striptease.jpg#/media/File:Striptease.jpg

- “Snow White Mirror 4” by Image provided by Landsbókasafn Íslands. Licensed under Public Domain via Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Snow_White_Mirror_4.png#/media/File:Snow_White_Mirror_4.png

Superb piece of writing. xxx

LikeLiked by 1 person

Are you open to your readers’ interpretation of the story?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Absolutely, Patricia! Fire away.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think possibly Judy was really ready to settle down and when she proposed to Dexter, he was conflicted between his logical self and his obsessive self. By following his desires, he had always made the best and safest choices but his logic told him that this would be a mistake. Also, once he ate the cake, there was nothing left to desire but he didn’t realize it because he was so used to pursuing Judy. He basically wanted what he couldn’t have as many of us do. We want something so badly because we think it is what we want and when we get it, we realize that it is not all we thought it was. We have failed to grow because we were living in the past. Been there done that. Judy wanted Dexter because she couldn’t have him, she was tired of being who she was. Yet she chose someone who was just like her because he was in her comfort zone. Even though her husband wasn’t what she wanted, she wanted him because she couldn’t really have him, not the way she wanted. What goes around, comes around. I wonder about how Judy’s father played into Dexter’s obsession if he did. I always overthink things so I may be all wet with my opinion but it was fun anyway. I often miss school.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think that’s a really valid interpretation, and it mirrors a lot of my own. I think there’s so much of a clue in Judy’s last name–Jones. A jones is a desire, and desires, once fulfilled, can’t be what they were anymore. She ends up with a man who doesn’t desire her, and thus, is no longer desirable (or Jones-ed for).

And Dexter’s last name–Green–is no less intentional. The money he has, but he can’t get past his “jones” for the “glittering things themselves” like Judy. And that being caught in the past thing is all the more present in The Great Gatsby, especially in the line “So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

I wondered what you meant by the Jones thing. Jonesing and Green maybe with envy also. You are awesome. Thanks for the challenge.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Exactly! Thank you for reading!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m decades away from the time I earned my Masters in English Literature, but still, I don’t think I ever received a better class lesson than the one you present here. I do know all the back history of Fitzgerald, and I’ve tried over the years to feel giddy about his writing. I’ve never been able to do so. Just last month I re-read Tender Is the Night. He goes on and on with the same theme in all of his stories, and at this time of my life (and fortunately, even when much younger), I could not relate to (nor did I want to relate to) his female characters, much less the male ones. But even so, I really enjoyed your post here! Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person