Dear Lily June,

It’s been awhile since I’ve subjected you to treated you with a Lit Lesson (at least one that wasn’t Benjamin Franklin inspired), and because, as your mother, I want to teach you about what truly matters in this life–love, empathy, compassion, and the literature that fosters these qualities in its readers–I can think of no better author to address from America than Frederick Douglass.

It may seem an unseasonable choice. Yesterday, after all, was your first Easter, a day during which you were surrounded by loving family, of both the given and chosen variety. My mom (your Grandma Raelyn), my stepdad (your Grandpa Derrick) and my half-brother (your Uncle Denny) all drove about six hours in a car just to see you (the last two for the first time ever).

It was a day of firsts, in fact. Your dad and I made Easter breakfast for them, and your mother baked hot cross buns from scratch for the first time, which I think will become one of our first Easter traditions. And small miracle, the yeast caused the dough to rise (so we weren’t forced to nick our teeth on hot cross bricks like I feared every moment leading up to eating).

That afternoon, after my family left, we went to our friends’ place for dinner, a veritable feast not just of food but of laughter and hugs and conversation. You were quite the entertainer, even though you can’t yet speak. You ooohed and aaahed into your forearms (your newest trick) and smiled at the people and shrieked in fear at the dogs (your first dogs!), and I felt so lucky just to be there, let alone to be your mother.

***

Getting in the Right Frame of Mind and Reading

It is with loving familial feelings in mind, Lily (which you, too, may experience when you’re old enough to remember them) that you should approach Frederick Douglass’ autobiography, My Bondage and My Freedom, especially the first three chapters, which you should, before reading on in this letter, go read from the links below. (Bear in mind, my version of the text that I quote may vary slightly):

I’ll be reproducing below large chunk quotations from these texts, so you could just skip reading the links above, but is that really how I raised you, young lady? To be so lazy?

[Insert mother glare here. You know the one.]

***

Understanding and Learning from the Times

The text was published in 1855.

You have to understand, Lily, that I taught literature and not history, so enumerating the complexities of an issue like slavery is so far above and beyond what I have the capacity to do, let alone in the brief space provided by a letter or blog post. Suffice it to say, our country was founded on a lot of terrible cruelty and human-to-human abuse. There was a time in America when a white man, merely by virtue of his being born white, thought it appropriate and right to enslave his fellow black man, for nothing more than that man’s having a different color of skin.

Africans were captured from their native country, forced into small shipholds in chains to sail across rough waters at great peril, and were dragged onto American land to work the fields and grow the crops and clean the homes and tend the children of the people who claimed to “own” them, who called themselves “mistresses” and “masters.” I put these words in quotation marks because, Lily, no person can ever own another like they might property or a home. There is no excuse, religious or economic or political or biological, that justifies the violence of slavery done in the name of all of these disciplines at the time.

We have entered a scary era in America today where similar excuses are being made to justify the violence done by everyone from neighborhood watch groups to the police against people of color. You need to know, Lily, that your mother feels race is just a social construct, part of the role we play as people in society. Biologically, we are all of us pink on the inside, and socially, we live our lives in the gray areas between who we really are and who others expect us to be. I know I should teach and not preach here, Lily, but this is too important to let slide:

NO ONE has the right to OWN, USE, or ABUSE another human being. NO ONE should use that person’s skin color as the excuse to do anything to them that they wouldn’t want done to themselves or their own loved ones. As proud as I am of you already for your learning to stand, I will be infinitely as proud if you learn to stand up for your own, and others’, rights.

Okay, so that’s the heavy. For the light, below (if it still works) is a Drunk History of Frederick Douglass. For being delivered by a speaker who’s completely inebriated, it’s surprisingly accurate. Pardon its French, though.

***

Understanding and Learning from the Author

In case you skipped the video, here are some important facts to know about Douglass:

- Born a slave, Frederick Douglass was most famous for his work as an abolitionist advocate. By the time of his death in 1895, Douglass was thought of in the United States and abroad as the most influential African American leader of the 19th century and as one of the greatest orators of the age.

- Douglass was even a friend and advisor of Abraham Lincoln during and after the Civil War.

- In addition to his work for the antislavery movement, Douglass was heavily involved in promoting the woman’s movement. His final speech, given just hours before he died of a heart attack on February 20, 1895, was at a women’s rights rally. Equality is equality, Lily.

***

Understanding and Learning from the Genre

Frederick Douglass actually wrote three autobiographies: Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass (1845), My Bondage and My Freedom (1855), and Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (1892).

This second autobiography, My Bondage and My Freedom, is supposed to be the most comprehensive in its discussion of families of the masters he had lived under, members of his own family, daily life in the great house and the plantation fields, and the mistreatment of slaves. See why I wanted you to have family in the back of your mind while you read it?

It’s an autobiography (or an account of someone’s life written by the person themselves), but it’s also a slave narrative. While slave owners were releasing political pamphlets encouraging the government to preserve a system of free labor with no consideration for the ethical consequences, these literary memoirs acted as a human response, detailing the physical and emotional experiences of enslaved Africans in Britain and its colonies, including the later United States, Canada and Caribbean nations. They put a face, voice and heart to a peoples long argued by their masters to have no more intellect or ability to feel than work mules.

While between six and ten thousand former slaves from North America and the Caribbean gave oral and written accounts of their lives during the 18th and 19th centuries, only about 150 narratives were published as separate books or pamphlets. Three of those 150 were Douglass’s. He speaks as one of the most eloquent abolitionist authorities in history. That means he deserves not just to heard, but for his words to be considered thoughtfully, with not just literary theory, but with your whole heart and personality.

***

Approaching an Autobiography Socially and Autobiographically

Back when I was in the classroom, Douglass day wasn’t one for dry dissection, analyzing every literary device and pouring over every metaphor until their magic was thoroughly explained. Instead, I asked my students to look over major passages in the piece as if they were looking into a mirror. Because the piece’s true aim was to inspire sympathy and to embrace common humanity between the slaves and the text’s often-free readers (not to dazzle, as it does, literary professors and students with its skillful rhetorical strategies and syntactical constructions), I’ll do the same with you, Lily.

Below, I’ve included memorable passages from those first three chapters, along with the questions I asked my students to relate to and consider aloud in classroom conversation. I hope you’ll consider everything you and Douglass have in common. I hope you’ll see the very significant ways your lives vary and you’ll understand that that, Lily, is what privilege is: when, by nature of who you are, how you’re born, and the society you’re born into, your life is easier than that of others.

I hope, by the time you’re reading, history isn’t repeating itself. And I hope, if it is, you’re in a place to fight the injustices you encounter–against you or others–along the way. I hope you’ll stand up and use your words, like Douglass does, to inspire others to dwell, not in our differences, but in the ways in which we are all the same. Anyone else reading this letter can join along, even using one of the questions below as a prompt to write their own blog or response. [If you do so, I will link to you, I promise!]

***

Comparing Douglass’s Life and Yours

Douglass on His “Setting”

“The name of this singularly uncompromising and truly famine stricken district is Tuckahoe, a name well known to all Marylanders, black and white. It was given to this section of the country probably, at the first, merely in derision; or it may possibly have been applied to it, as I have heard, because some one of its earlier inhabitants had been guilty of the petty meanness of stealing a hoe—or taking a hoe—that did not belong to him. …

That name…is seldom mentioned but with contempt and derision, on account of the barrenness of its soil, and the ignorance, indolence, and poverty of its people” (1240)

Your Thoughts on Your “Setting”

Douglass says of his birth that his hometown was hated, but it’s important to know where he’s from. That kind of information matters all the more to him, given inaccurate historical dating at the time, because he never knew exactly the year he was born.

- Would you say you’re from a town like this, where the people and place are looked down upon? Why or why not?

- Douglass says, “It is always a fact of some importance to know where a man is born.” Do you agree? Do you disagree?

- Does the year you were born say something about you? What, to you, does it mean?

Douglass on Family

“The practice of separating children from their mothers, and hiring the latter out at distances too great to admit of their meeting, except at long intervals, is a marked feature of the cruelty and barbarity of the slave system.

But it is in harmony with the grand aim of slavery, which, always and everywhere, is to reduce man to the level with the brute. It is a successful method of obliterating from the mind and heart of the slave, all just ideas of the sacredness of the family, as an institution” (1242).

Your Thoughts on Family

- Does knowing what your family members do for a living change your perception of your identity?

- Are memories of your grandmother an integral part of your identity?

- Is being close to your family essential to your life? (Oh, please, please say yes, Lily!)

- Is family a “sacred institution”? What, to you, does that mean?

Douglass on Freedom

“Living here, with my dear old grandmother and grandfather, it was a long time before I knew myself to be a slave.

I knew many other things before I knew that. …As I grew larger and older, I learned by degrees the sad fact, that the ‘little hut,’ and the lot on which it stood, belonged not to my dear old grandparents, but to some person who lived a great distance off, and who was called, by grandmother, ‘OLD MASTER.’ I further learned the sadder fact, that not only the house and lot, but that grandmother herself…and all the little children around here, belonged to this mysterious personage, called by grandmother, with every mark of reverence, ‘Old Master’” (1242).

Your Thoughts on Freedom

- Do you feel you are free to make your own decisions about who you are and what you want to be?

- Your fellow citizens in general today take their freedom for granted—Agree? Disagree?

- You take your freedom for granted—Agree? Disagree?

Douglass on Possessions

“If [the slave boy] feels uncomfortable from mud or from dust, the coast is clear; he can plunge into the river or the pond, without the ceremony of undressing or fear of wetting his clothes; his little tow-linen shirt—for that is all he has on—is easily dried…His food is of the coarsest kind, consisting for the most part of corn-meal mush, which often finds its way from the wooden tray to his mouth in an oyster shell.

…He eats no candies; gets no lumps of loaf sugar; always relishes his food; cries but little, for nobody cares for his crying; learns to esteem his bruises but slight, because others so esteem them.

In a word, he is, for the most part of the first eight years of his life, a spirited, joyous, uproarious and happy boy, upon whom troubles fall only like water on a duck’s back” (1244).

Your Thoughts on Possessions

- Your country puts too much emphasis on clothes—Agree? Disagree?

- You take your clothing for granted—Agree? Disagree?

- Your country puts too much emphasis on food—Agree? Disagree?

- You take your meals for granted—Agree? Disagree?

- People would be happier if they cared less about possessions—Agree? Disagree?

Douglass on ‘Home’

“The fact is, such was my dread of leaving the little cabin, that I wished to remain little forever, for I knew the taller I grew the shorter my stay.

The old cabin, with its rail floor and rail bedsteads up stairs, and its clay floor down stairs, and its dirt chimney, and windowless sides, and that most curious piece of workmanship of all the rest, the ladder stairway, and the hole curiously dug in front of the fire-place, beneath which grandmammy placed the sweet potatoes to keep them from the frost was MY HOME—the only home I ever had; and I loved it, and all connected with it” (1244).

Your Thoughts on ‘Home’

- Do you remember your childhood home? What are the dominant memories?

- Do you think the home you grew up in says something about who you are today?

- We shouldn’t build emotional attachments to places—Agree? Disagree?

Douglass on Siblings

“Grandmother pointed out my brother PERRY, my sister SARAH and my sister ELIZA, who stood in the group. I had never seen my brother nor my sisters before; and, though I had sometimes heard of them, and felt a curious interest in them, I really did not understand what they were to me, or I to them. We were brothers and sisters, but what of that? Why should they be attached to me, or I to them?

Brothers and sisters we were by blood; but slavery had made us strangers” (1246).

Your Thoughts on Siblings

- Do you have siblings (I hope so, Lily, but…) or such close friends you feel like they are “brothers” or “sisters”?

- Is your relationship with these siblings or friends an important part of your identity?

- Do you have extended family you’ve never even met? How do you feel about them?

Douglass on His Father

“I say nothing of father, for he is shrouded in a mystery I have never been able to penetrate.

Slavery does away with fathers, as it does away with families…and its laws do not recognize their existence in social arrangements of the plantation. …The order of civilization is reversed here. The name of the child is not expected to be that of its father, and his condition does not necessarily affect that of the child….He may be a freeman; and yet his child may be a chattel.” (1247).

Your Thoughts on Your Father

- Do you feel knowing who your father is affects your perceptions of who you are?

- Is your relationship with your father is an important part of your identity?

- Do you plan on following in the footsteps of your father in some way? How so, Lily?

Douglass on His Mother

“…I cannot say that I was very deeply attached to my mother; certainly not so deeply as I should have been had our relations in childhood been different. We were separated, according to the common custom, when I was but an infant, and, of course, before I knew my mother from anyone else. …Her visits to me…were few in number; brief in duration, and mostly made in the night.

The pains she took, and the toil she endured, to see me, tells me that a true mother’s heart was hers, and that slavery had difficulty in paralyzing it with unmotherly indifference” (1247-1248).

Your Thoughts on Your Mother

- Do you feel knowing who your mother is affects your perceptions of who you are?

- Is your relationship with your mother an important part of your identity? (If not, lie to me, baby!)

- Do you plan on following in the footsteps of your mother in some way? How so, Lily? (And yay!)

Douglass on Kindness

“That night I learned the fact that I was not only a child, but somebody’s child.

The ‘sweet cake’ my mother gave me was in the shape of a heart, with a rich, dark ring glazed upon the edge of it. I was victorious, and well off for the moment; prouder, on my mother’s knee, than a king upon his throne” (1249).

Your Thoughts on Kindness

- Can one moment of well-timed kindness change how you feel about your life?

- Have you, at least once, tried to change someone else’s life with a random act of kindness? If so, how and for whom?

- Has your life has been changed by someone else’s kindness? If so, how and by whom?

Douglass on Education

“I learned, after my mother’s death, that she could read, and that she was the only one of the slaves and colored people in Tuckahoe who enjoyed that advantage…

That a ‘field hand’ should learn to read, in any slave state, is remarkable; but the achievement of my mother, considering the place, was very extraordinary; and in view of that fact, I am quite willing, and even happy, to attribute any love of letters I possess, and for which I have got—despite of prejudices—only too much credit, not to my admitted Anglo-Saxon paternity, but to the native genius of my sable, unprotected, and uncultivated mother—a woman, who belonged to a race whose mental endowments it is, at present, fashionable to hold in disparagement and contempt.” (1249-1250).

Your Thoughts on Education

- Your country, generally, takes literacy and education for granted—Agree? Disagree?

- You take your education, and the right to it, for granted—Agree? Disagree?

- Your ability to attend school is a large part of your identity—Agree? Disagree?

Douglass on Death

“After what I have now said of the circumstances of my mother, and my relations to her, the reader will not be surprised, nor be disposed to censure me, when I tell but the simple truth, viz: that I received the tidings of her death with no strong emotions of sorrow for her, and with very little regret for myself on account of her loss. I had to learn the value of my mother long after her death, and by witnessing the devotion of other mothers to their children.…My mother died when I could not have been more than eight or nine years old, on one of old master’s farms in Tuckahoe, in the neighborhood of Hillsborough.

Her grave is, as the grave of the dead at sea, unmarked, and without stone or stake” (1250-1251).

Your Thoughts on Death

- Can you empathize with Douglass’s feelings about his mother’s death in some way? (Say it ain’t so, Lily!)

- When you die, do you want your grave to be marked and made known? Why or why not?

- The ability to grieve the loss of a loved one is an important part of love—Agree? Disagree?

***

Lily June, I know this is a lot to consider all in one day but the most brutal aspects of history (in this case, slavery) and their counterparts (here, the abolitionist movement) are worth a lot of reading, research, conversation and consideration in order to make you a more thoughtful member of the human race in general and of your country, specifically. In an era of TLDR, I have to give thanks to you (and any other reader) for taking this LONG journey with me.

I hope you learned something about Frederick Douglass and, just as importantly, I hope you learned something about who you are and the kind of person you want to be.

***

Picture Credits:

- By Engraved by J.C. Buttre from a daguerretotype. – Frontispiece: Frederick Douglass, My Bondage and My Freedom: Part I- Life as a Slave, Part II- Life as a Freeman, with an introduction by James M’Cune Smith. New York and Auburn: Miller, Orton & Mulligan (1855), Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3083385

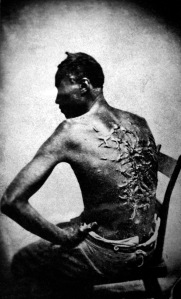

- By Original photographers: McPherson and Oliver. Part of the Blakeslee Collection, apparently collected by John Taylor of Hartford, Connecticut, USA – Archive national des États-Unis – National Archives and Records AdministrationThis media is available in the holdings of the National Archives and Records Administration, cataloged under the ARC Identifier (National Archives Identifier) 533232.Downloaded from: http://teachpol.tcnj.edu/amer_pol_hist/thumbnail193.html, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=284064

Works Cited:

- Douglass, Frederick. “From My Bondage and My Freedom.” The Norton Anthology of American Literature, Vol. B. Ed. Nina Baym. 8th ed. New York: Norton & Company, 2012. 1240-1250. Print.

DLJ, since I have been in the mood for a post such as yours, and having only just been finding the time to read again…I’m heading to library to get this book (unless the less obvious anxiety keep me here, then only with a phone but readable none the less from the bottom half), and read it. I will then turn in my homework to you on the first three chapters, in hopes to learn something about a something I have never experienced, but long to understand…as compassion and empathy are often not enough when living in the grey areas of our lives.

While I have yet to finish reading this work in its entirety, do thank your mama LilyJune! For loving you so much she sees beyond herself and the grey daily, for you. And tell her I admire her passion for her work that is you, with you, for you. You look just beautiful by the way.💜

LikeLiked by 1 person

My home state recently passed a piece of legislation which I view as a step back toward the shameful days of its past, and if that wasn’t bad enough, did so in a manner in which I find disgraceful. Unfortunately, events like that have proven that I am going to have to keep posts like this (beyond excellent by the way) on file for on-going discussions with my children who I hope will one day be completely baffled that practices like this ever occurred.

And she’s adorable. Happy Easter.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have to say I really enjoyed this even though it brought tears to my eyes and it made me quite sad. It is history and one that I know so well but I appreciate how well you put this together. As you said, by the time Lily gets older, I hope we aren’t going back that way or History is not repeating itself. Thank you for a wonderful post. Happy belated Easter to you all.

LikeLiked by 2 people

That’s why I think it’s so important for Lily to have that sense of history. Her society may try to repeat the same discrimination and hate that led to such cruelty, but if she knows where it comes from, she can stand against that tide. The whole thing brings tears to my eyes, too, and I just can’t understand why these things ever had to happen. I will teach my daughter another way to be, to live with and to love EVERYONE she meets and to never exploit another human being.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I loved the Posts. I think Douglass would be proud of this tribute. I must say that this is a heavy but necessary lesson for all children. Very well written. I love the Easter dress picture. I’m sure you just “eat her up”!

LikeLiked by 1 person

So much fodder with which to write.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great post! These are such important topics to discuss and questions to were answer. I would like to read Douglass’ books as well as some of the 147 others. I was reading a Bell Hooks quote yesterday, “No black woman writer in this culture can write “too much”. Indeed, no woman writer can write “too much”…No woman has ever written enough.” I think the same applies to these slave narratives. No matter what their form, each one has a perspective and voiced that was brutally silenced by white people. I think it so sad that there are only 150, when there were so many more unique stories that should have had the chance to be told. So much history lost and it makes me worry that so many stories are still being lost due to institutional racism, and the lack of diversity in various creative industries due to that institutional racism, or the fact that white narratives are often considered the norm or standard. So glad you write this blog!

LikeLiked by 1 person

And of those 150 that were separately published in stand-alone form, how many are equally accessible in the country to *anyone* who wants to read them? That’s why I want Lily to know about them. Maybe she will or won’t go to college, but I was rarely exposed to slave narratives in high school, and I think they’re so important for giving a clearer picture of history than dates, figures and statistics alone.

No voice should be silenced.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I agree with your points about race and also share some of the misgivings you hinted at about the willingness of certain unscrupulous politicians to use it to political advantage. I was particularly interested to read about the fact that Douglas’s mother could read. That couldn’t have been easy given her circumstances at the time.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You are giving LilyJune a great gift! Thanks for your thorough article here, and for your care to speak to this. Here’s my clumsy way of working through race: https://moreenigma.wordpress.com/2014/12/18/why-american-race-relations-affects-me-as-a-german-canadian/

LikeLiked by 1 person